Reading Better

For elementary and middle school-aged students, reading better, in their minds, often means simply reading faster. While reading fluency and words per minute (wpm) are crucial indicators of a strong reader, a student whose primary goal is to read quickly is not necessarily reading properly. To curb this “faster is always better” mentality while still promoting fluency growth, parents and educators can help shift the focus to a more broad definition of a strong reader.

- Strong readers do much more than absorb and store the information that they have read in their minds. Recall is important, but application is more important. This means that, after students read, an immediate process or task to apply that information or combine details from the text with another skill is critical.

- After reading about ancient civilizations, for example, ask students to participate in a discussion in which they compare ancient tools and building methods to today’s modern tools and structures.

- While reading a “how-to” text, ask children to restate each step in order using the text. Then ask them to consider why certain steps must be completed before others.

- When reading a novel or story, encourage students to make connections to the text with questions and considerations, such as:

- Why do you think the character responded in that way?

- How do you think he/she is feeling at this point in the story, why?

- Have you ever felt that way or experienced something similar?

- What would you do if you were in this same situation?

- What kind of relationship do these two characters have? How do you know?

- Do you think the character is making good decisions?

- What do you think might happen next based on what we have read?

- Have you read anything like this before?

- How was that story similar or different?

- Does this story, setting, conflict, or character remind you of anything you have heard or watched before?

- If students are asked to complete a multi-step assignment or required to read complex or lengthy directions, encourage them to break the steps or directions down into smaller, manageable procedures. Prompting students to rephrase instructions or directions is also a good practice for applying what they have just read.

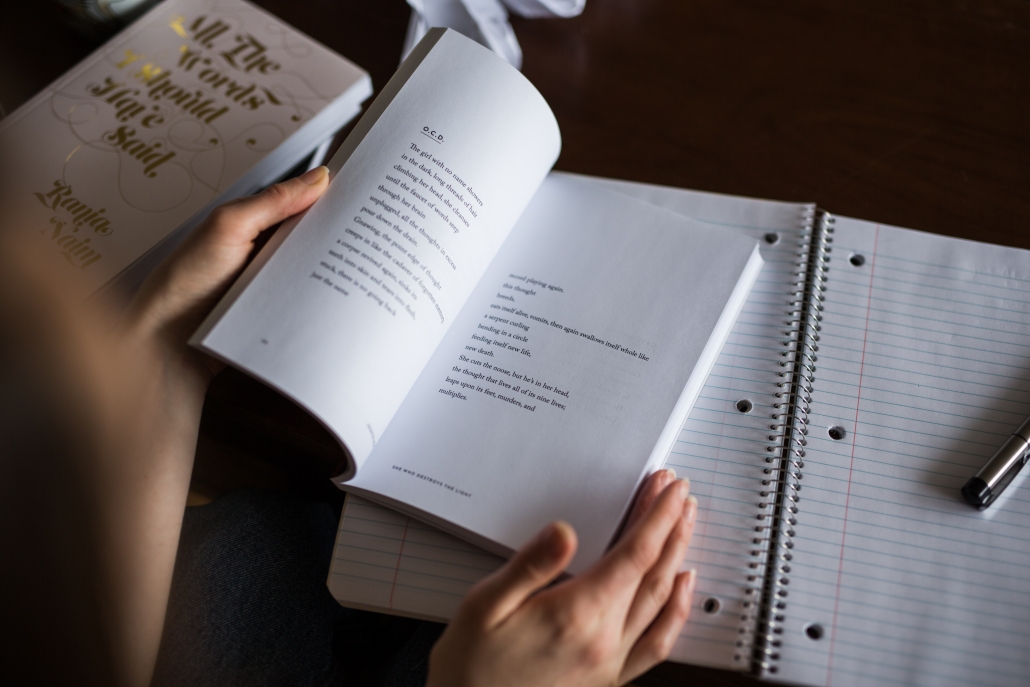

- Teach young readers how to consider their intent for reading whatever it is that they are reading. When reading for pleasure, their reading strategies might include making predictions, visualizing the details of the story, or discussing the section or page with a friend who is reading the same novel. However, if a student is reading something for school, the strategies are likely different because of his or her intent.

- Ask students to consider their goals for reading prior to diving into the text. Do they want to memorize certain information? If so, rereading is going to be a necessary process for that text. If a student is reading something to learn a new skill or strategy, they may want to summarize or simplify the text as they work through each page or chapter.

- Similarly to goal-setting before reading, teachers should encourage readers to consider one thing that they hope to gain from the text. Are you seeking another’s perspective? Absorbing new vocabulary? Looking for clues to a math word problem? Comparing/contrasting information? Summarizing a process? Investigating a problem and potential solutions? Following a sequence?

- Ask students to then identify if their goal or intention was accomplished or met by reading the text. If not, ask them to question why they may have missed the mark while reading.

Discuss what active reading looks like. For many students, especially reluctant readers, reading simply means getting to the end—each page or paragraph is just one step closer to being finished. When completion is the goal, students tends to daze, daydream, and lose focus of the text. Remind students that, if they get to the bottom of a page and realize that they had been thinking about something completely different from the actual text, they were not actually absorbing the information. This is similar to the difference between seeing something and looking at something—sounds like the same thing, but looking at something means to examine it; seeing it means to just come across something without actual consideration.