Combatting Stress in the Classroom

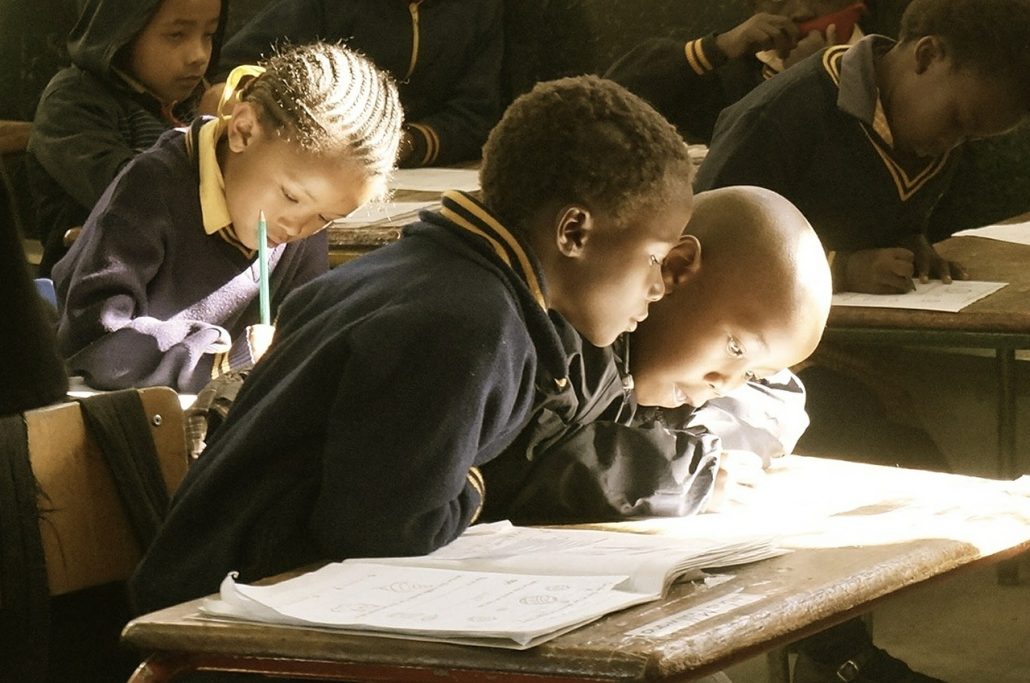

Illnesses in the classroom are inevitable. The highly social aspect of the classroom is one of the great parts of education—students working and learning closely together. Unfortunately, the flipside to this is that germs are spread in these enclosed social realms very, VERY easily.

As many parents are well-aware, students fall ill most frequently during the winter months. Whether it be a cold, stomach bug, or full-on flu, students are most susceptible during the colder months because of the tendency to remain indoors, where germs are more easily transmitted. Physical illnesses, however, are not the only noticeable health issues in the classroom. As teachers, we are also well-aware of the fact that school can be a major turning point when it comes to recognizing mental health issues in adolescents.

Yes, Lysol and antibacterial wipes go a long way in the classroom in terms of keeping our students healthy. However, much like the invisibility of dangerous germs in the classroom, mental health issues can be even more difficult to detect. Of course, school counsellors are much more knowledgeable when it comes to formal diagnosis, but teachers should know what to look for as well. One major indicator can be how a child responds to stress.

Stress can have a major impact on student success and well-being. As much as we try to minimize stress on our students, academia inevitably puts young people into stressful situations. Stress-management is a vital skill for students to acquire in their primary and secondary years of school, but what does it look like when stress becomes too much? When is it overwhelming on a destructive level?

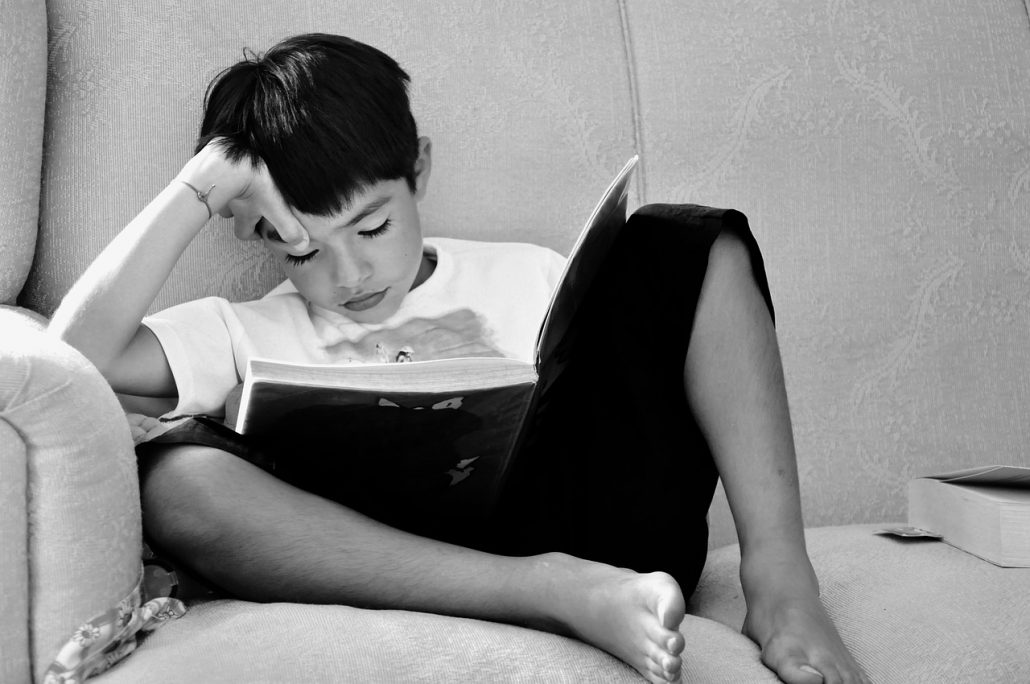

Extremely stressed students will appear extremely lethargic, disinterested, or sluggish in the classroom. This low energy is a physical response to stress, anxiety, and/or depression. When things become overwhelming, adolescents sometimes cope by “shutting down.” Lethargy is a means of “checking out” or evading whatever it is that is stressing them out. It is also a sure sign that a student is not getting enough sleep due to stress or worry.

Task avoidance is another layer of low energy exhibited by stressed students. This can be marked by missed assignments, a sudden drop in grades, or an increase in school absences. Avoiding tasks or school altogether is a more direct manner of evading the stressors. The issue, however, is that missed school will only result in escalating the problem of falling behind, thus increasing stress.

Repetitive or ritualistic behavior could be an effect of anxiety caused by stress. Often a symptom of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), the subtle routines become methods to self-soothe or irrationally alleviate stress. Students may also blink, tap, fidget, etc., as a distraction technique when they begin to feel overwhelmed.

Sudden social issues are another sign that stress has reached an unmanageable level for adolescents. Because peer groups shift regularly and unpredictably, these “friend fluctuations” are difficult to distinguish as stress-related, or simply teenagers being teenagers. The key here is for teachers to recognize social withdrawal versus shifting friendships. A previously social or congenial student who suddenly appears lonely, withdrawn, or isolated is likely experiencing stress or anxiety. When this extreme introverted behavior lasts continuously for any length of time, it is important to look deeper at the situation.