Building a Strong Vocabulary: Secondary Level

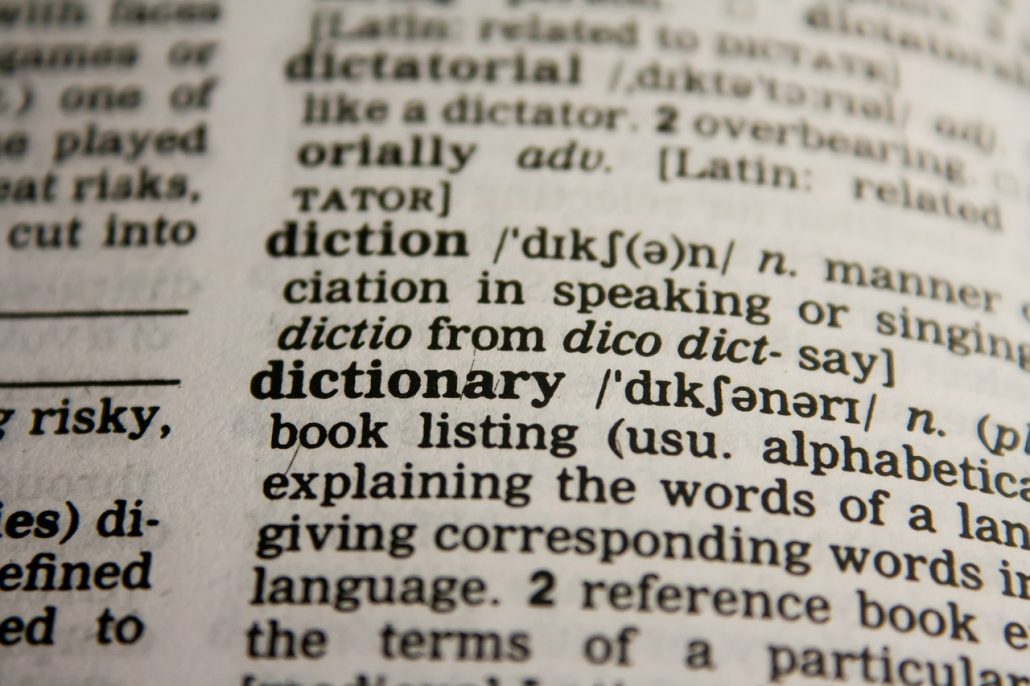

Comprehensive studies estimate that there are likely three quarters of a million English words, and this is a conservative estimation. With seemingly limitless options to choose from when speaking, writing, or reading, vocabulary acquisition is a vital, albeit somewhat disregarded, aspect of academic development. Surprisingly, many schools greatly limit vocabulary instruction after a certain grade, some even forgoing it altogether. So, how exactly can we foster a rich vocabulary for teens as they work their way through the upper grades?

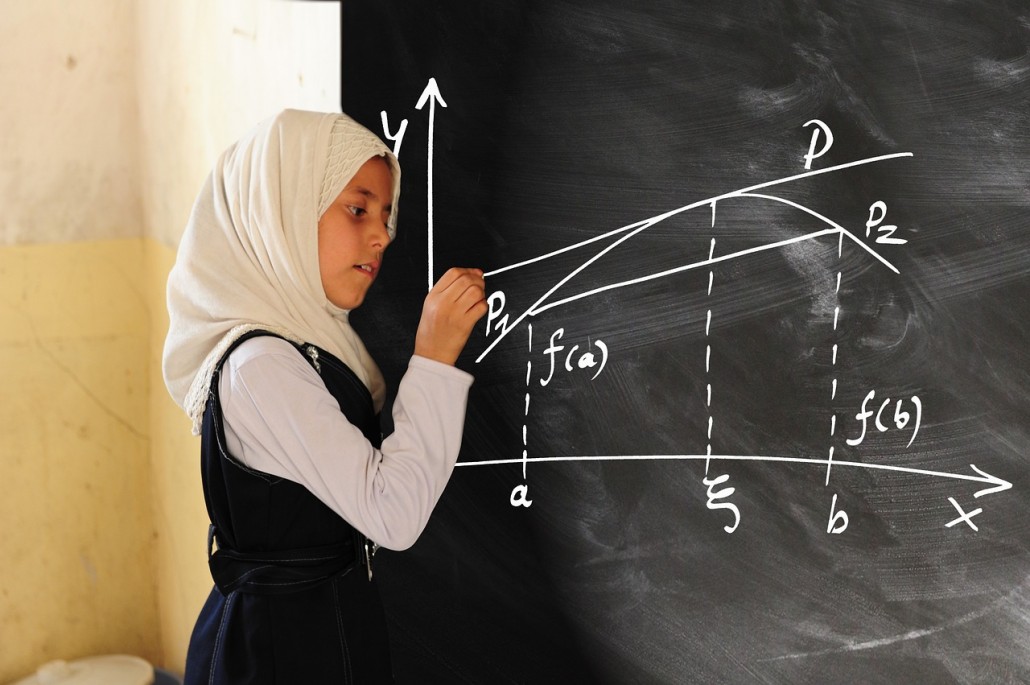

Use theater practices or role play to encourage alternate ways of communicating. The idea behind these types of activities involves the practical uses of vocabulary. One major benefit, if not the most important gain from having a vast vocabulary, is the fact that it allows us to be chameleons, so to speak. The more ways that we can express ourselves, the better. Vocabulary is a key component when speaking for different purposes, audiences, or scenarios. When employing certain vocabulary, you are making a conscious decision about how to appeal to the person or persons with whom you are speaking. A sign of intelligence, as well as a major benefit for college and career-ready students, is the ability to alter speech and vocabulary for various circumstances. The more you can practice “playing” certain roles, the better.

Studies suggest that direct instruction of vocabulary does little to build an understanding. Word games, however, are a fun and easy way to practice building vocabulary at any age. Scrabble, Boggle, and crossword puzzles will provide students with skills to build a robust vocabulary. Even using an activity such as Mad Libs can help teens practice vocabulary use in a “play-like” format. Utilizing word games is a great way to build motivation and comprehension without making it seem like instruction.

Incorporating synonyms is another valuable manner of building vocabulary. When your teen is expressing emotions, prompt him or her to use other words beyond “mad,” “sad,” and “happy.” Expressions, actions, emotions—the categories are limitless for introducing synonyms. The point here is to provide as much exposure as possible. Even when speaking around your teens, introduce advanced or unfamiliar words so that they can hear them being used in everyday speech. When doing this, be sure to provide adequate context so that the new terms are rooted in speech or language that they already know. Otherwise, the new terms will be literally lost in translation.

Reading is a very obvious, yet necessary aspect of building a strong vocabulary. When adolescents encounter new texts, they are bound to face new terms, as well. Reading is a natural way to use context clues for vocabulary acquisition. Not every word meaning is going to be handed to a reader—the text will make the reader work for it. Encourage your middle or high schooler to recognize and pause when a word is not decipherable through the context. After rereading, if the word is still unidentifiable, prompt him or her to look it up. Nowadays, technology literally puts resources in the palms of students’ hands. Two seconds is all it takes to add that new definition or understanding to a teen’s repertoire.