Classroom Strategies for Students with Asperger’s

As of 2013, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has reclassified Asperger’s syndrome to include it in the broader category of autism spectrum disorder. Unlike some other conditions along the spectrum, children with Asperger’s syndrome are considered “high-functioning.” This means that children and adults with Asperger’s experience are intellectually and verbally advanced, yet experience social and/or executive functioning deficits.

Asperger’s syndrome can be frustrating for the child and those closest to him/her. Since classrooms today involve constant social components, students with Asperger’s will likely require certain routines and strategies to help facilitate their interactions with peers and adults in and outside of school.

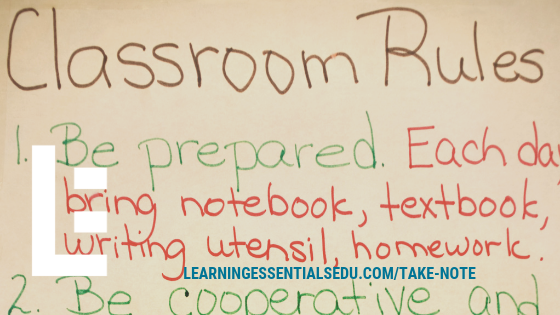

Maintain consistency

Students with any form of autism spectrum disorder thrive when they know what to expect—surprises, disruptions, or diversions from the norm are not favorable and can cause unnecessary stress. This means that teachers should specifically and deliberately introduce routines, expectations, and basic classroom guidelines and adhere to them so that all students, but especially those with Asperger’s, can adapt to the established expectations. Things such as warm-ups, explanations for homework assignments, routines for moving around or asking to leave the room—even the location of the pencil sharpener—should remain consistent.

If, for whatever reason, a classroom routine or school schedule must change, be sure to explain the modification to the student directly—do not just assume that he will anticipate or grasp the change. Additionally, provide a logical reason for the change. For instance, if a fire drill or weather delay has adjusted the bell schedule, make a note to print, post, or explain the day’s modified schedule and explain that the change was made to account for a shorter school day or disruption in the schedule.

If students have unstructured or unsupervised time, such as lunch time or transitions in middle and high school, help the student to understand what his options are during lunch and between classes, the time constraints to complete those options, and his best method or route for navigating to the next class on time.

Be direct

While students with Asperger’s may have an advanced vocabulary, their ability to communicate their feelings or perceptions, as well as their ability to interpret someone else’s, may be lacking. For this reason, sarcasm, exaggerations/hyperbole, euphemisms, puns, or vague expressions are often misinterpreted or confusing to students with Asperger’s syndrome. Instead of beating around the bush (see what I did there?) or using indirect phrasing, be explicit with students so that they know exactly what is being communicated. For instance, if students are about to dismiss, saying, “relax until the bell rings” could mean many different things. Instead, tell students to “remain seated quietly at your desk until the bell rings.” With a direct statement, there are no misinterpretations or misunderstandings.

Provide clear options

Decision-making can be a difficult undertaking for students with Asperger’s syndrome—they may become overwhelmed by their choices or worry about selecting the “best” option. It is beneficial for teachers to provide student choice, but limit the scope of those choices for students who struggle to synthesize information.

For example, if students are selecting one of the seven wonders for a research project, consider asking certain students what their top three wonders would be. Then discuss as a small group and model decision-making strategies. Ask students things like, “Which location do you think is the most famous or would have the most accessible information?” “Do you have background knowledge of any wonders on your list?” “Which wonder are you most curious to learn about?” “What part of the world is most intriguing? Might you choose a wonder located there?” These questions direct students to think analytically about their options, which helps when choices seem random or arbitrary.

Deescalate the situation

Children with Asperger’s syndrome may have a lower threshold for irritation or annoyance, which can increase the likelihood of meltdowns in the classroom. Teachers and counselors can take proactive steps to avoid or diffuse situations when tempers flare in the classroom. Connect with parents early on—they will be able to cue you in on what might irritate or annoy their child in particular. They are also likely to have strategies for diffusing situations when they arise.

Consider a designated “cool down area” within the classroom equipped with flexible seating, stress balls, sketch pads for doodling or journaling, and noise-cancelling headphones. Especially for elementary and middle grades, these quiet corners allow all students the option to remove themselves from a potential conflict to regroup or decompress. This quiet, stress-free zone is especially beneficial to students with Asperger’s syndrome because frustration for them can result in all-encompassing meltdowns.

Checklists/check-ins

Since students with Asperger’s often experience gaps in executive functioning skills, teachers can use simple strategies to help fill those gaps and introduce students to new methods for self-management. For complex tasks or multi-step assignments, a visual checklist can help younger students visually account for essential pieces of the assignment. The checklist also guides students as they plan and execute a project in logical order.

In addition to a checklist or to-do memo, teachers should plan to meet frequently with students to ensure that components are being completed and progress is getting made during independent work time. A tentative calendar or weekly work schedule could also help students to manage their class time, complete tasks in order of importance, and practice self-monitoring as they work their way through the week.