Tough Conversations: A Tool for Parents, Part II

Now that we have scratched the surface of the compass from Singleton’s “Courageous Conversations about Race,” it is time to discuss exactly how parents can utilize the compass when having other courageous conversations with their teens. While the compass was originally designed as a method for structuring respectful and productive conversations around race, the same philosophies can apply when tackling tough discussions with teens at home.

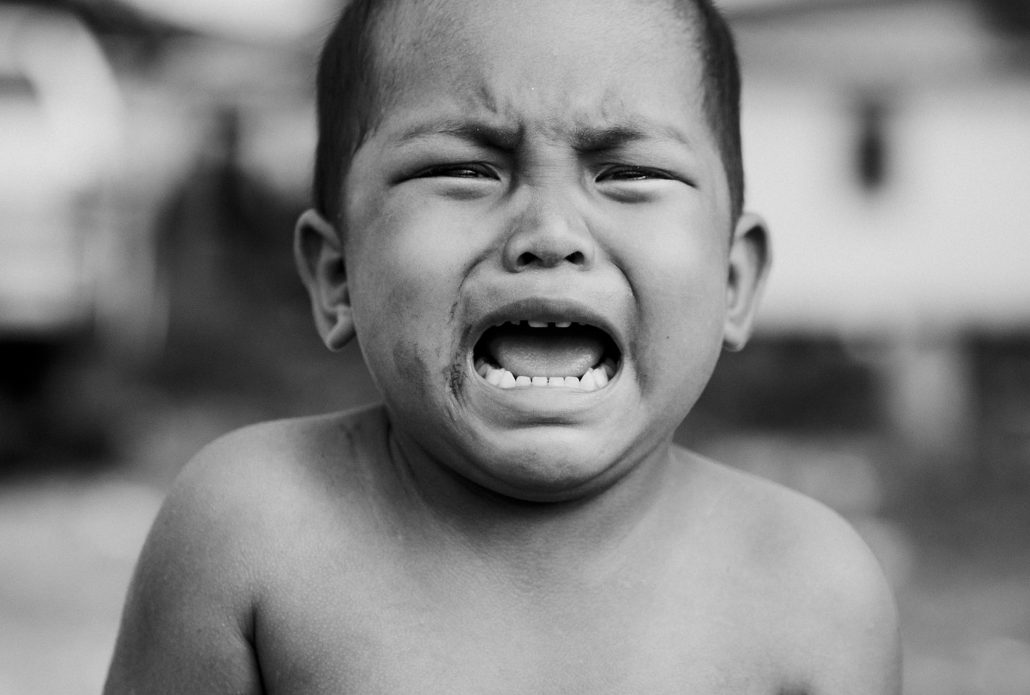

Recognize and Validate an Emotional Viewpoint

Understand that, hormonally and developmentally, it is probable that many debates or discussions with your teen will result in your child entering and participating in the conversation from the emotional axis of the compass—and this is okay. Help your teen recognize when he or she is entering the conversation from an emotional angle by first validating his or her feelings. Simply acknowledging their feelings by starting with, “I see that you’re upset and I understand why” will allow teens to remove any defensiveness if a discussion becomes emotional on their end. Remind them and yourself that emotions can run high, and a conflict or argument can greatly benefit from some breathing room. If the discussion becomes combative or unproductive, allow your teen some time to pause, settle, and reflect before proceeding with the conversation. In the heat of the moment, emotions can take over, allowing no room for seeing someone else’s point of view.

Capitalize on Opportunities to Discuss Morality

Entering an important or intense conversation from the moral quadrant of the compass can be an enlightening experience for parents and teens. Let’s say that your teen was caught cheating on an exam. When discussing the situation, approach their misstep from a moral angle. First, ask why they decided to cheat—did they not study enough? Were they afraid of the possibility of failure? Were they trying to appease you with a good grade? What prompted this decision to cheat? Their answer will act as your springboard for discussing the moral implications of cheating. If the fear of failure is what spurred their decision, discuss that success is much more than a letter grade—true success or achievement means reaching an authentic goal or milestone, and there is nothing authentic about a grade that you didn’t earn. Allow them an opportunity to discuss how they quantify what is moral or right versus behavior that is immoral or inherently wrong.

Cold-hard Facts Can Help a Teen See the Light

An intellectual or level-headed approach to a conversation is easier said than done, especially when dealing with adolescents. When parents find themselves in a discussion, debate, or all-out conflict with their teen, it may help to have some fun facts on their side. Encourage your teen to look at the logical approach to an issue by presenting them with sound reasoning or resources to do the searching themselves. When teens have the opportunity to seek logical reasons for or against an important decision, they are less likely to make rash or rebellious decisions. Avoid playing the “know-it-all” role by helping them seek answers, as opposed to throwing answers at them or blatantly coercing their viewpoints.