National Handwriting Day: A Spotlight on Dysgraphia

Contrary to the common misconception, dysgraphia is a learning disability that signifies a more serious problem than a simple inability to write neatly or color inside the lines. Yes, dysgraphia often manifests itself in the form of “sloppy” or illegible handwriting; however, the difficulty arises before the pencil hits the paper. Dysgraphia is actually a processing disorder, meaning that the deficiency comes from the inability to receive input or construct output of information from the senses.

Each learner is different, so dysgraphia can present as a struggle to perform the physical, motor-controlled aspect of writing, or the mental, expressive aspect of synthesizing thoughts and organizing them on paper. It may help parents or educators to think of dysgraphia in terms of a quarterback on a football field—the disability might cause the QB to physically struggle to grip, hold, pass, or hand off the ball. However, he might also struggle with the mental or decision-making aspect of when to throw a pass versus make a run. Either way, the deficiency in sensory input or output can disrupt his success on the field, much like a student’s academic success in class.

Here are a few suggestions for addressing the physical aspect of dysgraphia:

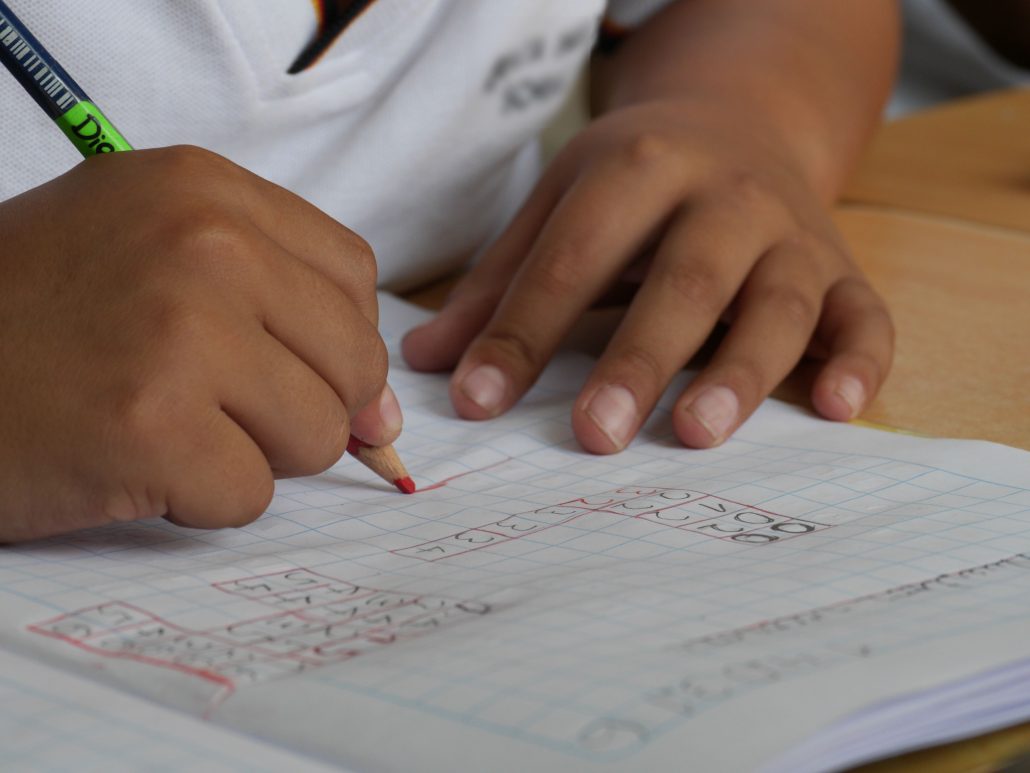

For young writers with dysgraphia, the physical act of writing can be cumbersome. The deficiency does not come from a lack or care or effort. In fact, many students with dysgraphia are putting extra effort into their handwriting, but may still be coming up short. To help those who struggle with their motor skills when it comes to letter legibility, spacing, size, etc., parents, teachers and therapists can employ multiple strategies or best practices to help the child’s writing.

Some young learners may benefit from using paper with raised or perforated lines to assist with letter size and spacing. The tactile element helps to make children aware of the physical boundary lines between which their letters should remain. Similarly, tracing practices with raised outlines are also available. When students practice tracing either on paper or in the air using “imaginary letters,” encourage them to form letters the same way every time. For instance, when practicing the letter C, make sure that children start with their pencil at the top, arching counter-clockwise and down to form the letter. Repetition of movement is key when strengthening muscle memory to improve writing, so remind them to construct the letter C the same way every time.

Consider providing multiple shapes and styles of pencils or pens. Sometimes rubber pencil grips can help with the discomfort that children with dysgraphia experience. Some students find that hexagonal or three-sided pencils feel more stable than perfectly round pencils, or vice-versa.

Writing can be extremely frustrating, so motivate children by keeping writing practices or tasks brief and to the point. When hands and fingers become tired or cramped, writing can range from uncomfortable to painful—take a break long before any discomfort sets in to maintain effort and motivation. Encourage students to focus on one aspect of their handwriting at a time. Perhaps for one assignment, this means that a child will work primarily on his/her letter spacing within and between words. Next time, he/she might focus his attention on the sizing of capital letters and lowercase letters. Breaking up the writer’s goal can help make handwriting less daunting.