Homework Strategies for Easy and Effective Practice at Home

Now more than ever, students are experiencing astounding amounts of work outside of school. Instead of an hour of homework per night, many students and parents are now seeing an hour of work per content area each night. Depending on grade level, this may mean as much as 5+ hours of homework on any given school night. With so much time going to homework, it is important to make sure that work time at home is as stress-free as possible. So, how can parents help to alleviate homework woes? It is as easy as 1-2-3.

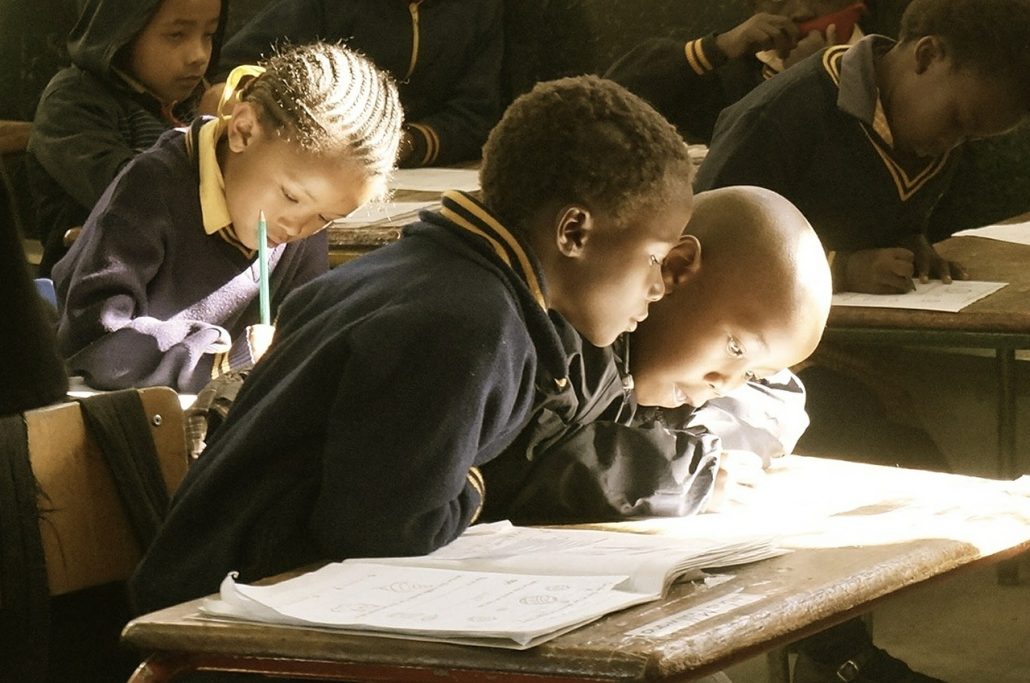

Praise effort. Much of the stress affiliated with homework revolves around the ideal of homework perfection. Yes, correctness is important, and students need to be ready to exhibit mastery when it comes to major projects and assessments. However, the everyday homework assignments that come home are likely for practice—not perfection. Instead of hours of struggling to arrive at the correct answer for every question on every assignment, encourage the honest effort put forth. The importance of homework is to provide opportunities to practice and seek clarity for new concepts or skills. Students should feel allowed to make blunders or experience difficulty when completing homework so that they are prepared to ask questions, analyze errors, and reflect on their practices when they arrive back in the classroom.

So, if you find your child in tears or stressed over the presumed need to arrive at the correct answer for every homework assignment, remind him that practice involves making mistakes. Errors not only help young learners to develop grit and determination, but they also allow students to begin to understand themselves as critical thinkers.

Speak with teachers about homework issues—and encourage your child to do the same. When homework, projects, and exams seem to be weighing down the dinner table, chances are the stress is weighing on your child as well. When this happens, reach out to your child’s teacher(s) about your concerns. Send a quick email or a note to school expressing how hard your child worked on the assignment, but that is was not possible to fully complete the work. Again, effort is the key—and teachers will understand that the student truly attempted the work. Homework is meant to be a scaffold or support, one which provides students with opportunities to practice skills. But, if the assignments are too lengthy, redundant, or complicated, students are likely to shut down or break down at home—neither of which is beneficial to academic success.

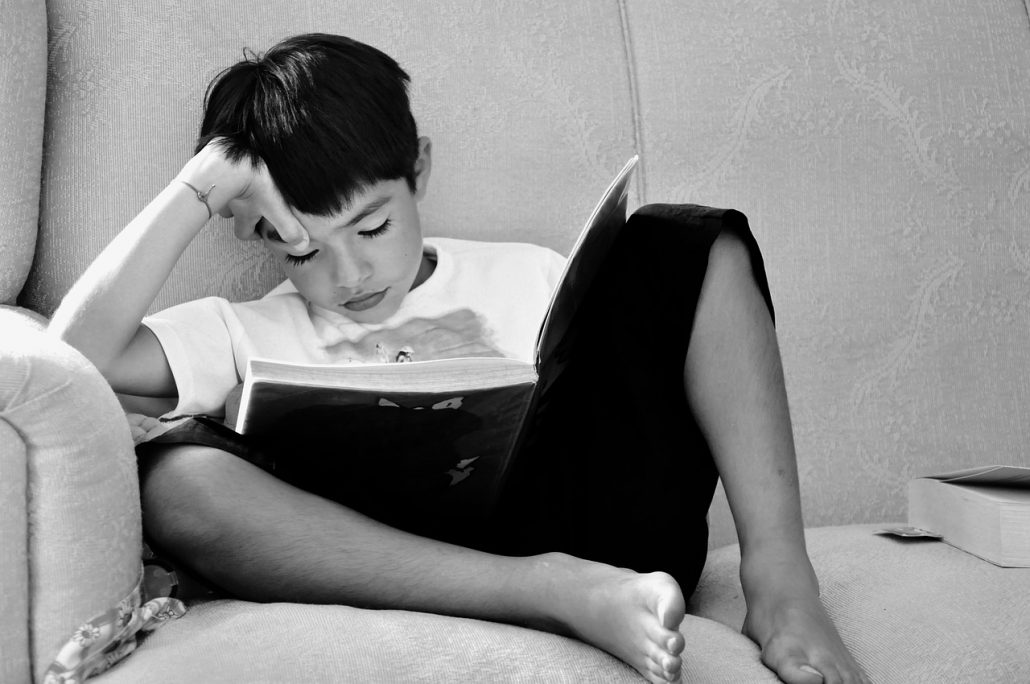

Remove distractions—all of them. Parents must set the tone for effective homework time. Allow children to choose a comfortable, quiet area to settle in and complete assignments. Make sure that their workplace is well-lit and contains everything that they will need to work in terms of supplies and work space. Remove distractions such as iPads, cell phones, television, etc. Parents can set a good example by picking up a book and reading quietly while children complete homework.

Providing short breaks between assignments or lengthy projects will help as well. Energy and focus start to lag when working for long stints of time. Encourage your child to take a short 5-10 minute break every 45 minutes or so. Eating a little snack and grabbing a bottle of water while taking a brisk walk around the block will help to rejuvenate and refocus a child who has been working steadily.

Creating a checklist adds to the gratification of completing assignments at home. Much like the to-do lists that we all create, children can also benefit from the checklist in multiple ways. A checklist ensures that children know exactly what must be completed in a given block of time. It is a studious practice—one which helps to keep youngsters organized and promotes self-advocacy. Not only that, but creating a list of assignments is a simple method of boosting intrinsic motivation—crossing off tasks as they are completed is a great way to acknowledge the hard work.