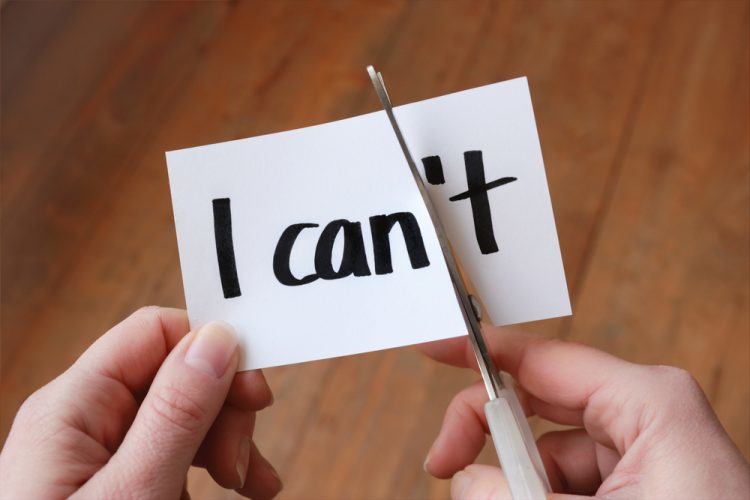

How to Break the Negative “Can’t Do” Mindset: Elementary

In elementary school, children are just beginning to understand themselves as learners. These are crucial years in terms of building a positive mindset and a solid understanding of education and its significance in their lives. Because of their blossoming ideas and new experiences in school, elementary-aged learners can be especially fragile when it comes to their self-perception.

One surefire way to turn children off to school, education, and all things learning-related is to allow them to steep in their own negativity. This “I can’t” mindset can be especially detrimental to young learners because the longer they engage in this negative self-fulfilling prophecy, the more likely they are to solidify those beliefs as true. To combat the cycle of negative self-perceptions, teachers and parents can implement different exercises, practices, and conversations to encourage a positive outlook.

Abolish terms like hard, boring, easy, and fun when describing an activity, assignment, or task. Instead, replace those descriptions with words like challenging or interesting. A subtle shift in the adjectives removes the opportunity to equate the school work with a negative connotation. If something is described as a challenge, as opposed to hard, children are more likely to muster the effort and be motivated by the opportunity to try. Similarly, abandoning anxiety-producing terms such as test or exam can also bolster a more positive outlook.

Do away with thinking of education in terms of absolutes. Because of the way that our educational systems are structured, learners often get caught up in the “all or nothing,” “pass/fail,” “smart or not smart” mentality. Cultivate the notion that school, learning, and intelligence are not exclusively yes or no categories. Sentences like, “I’ll NEVER understand this!” are only serving to prove that negative belief. Instead, instruct students to adopt a growth mindset when engaging in self-talk. Examples might include, “This is challenging, but I’ll keep trying.” “The more I practice, the better I will become.”

Stress the importance of growth over perfection. Again, much of our standard ideas of education involve grades, percentages, and correct answers. But to prepare elementary schoolers to become lifelong learners, adults must put the focus on overall growth and acquisition of new skills.

Present school work and learning in general as a lifelong, continuous process. It is important for children to know that there is not one person who knows everything about everything—and no, you are never “done” when it comes to learning. Remind elementary schoolers that because curiosity is what feeds our need to learn, it is okay, even expected, that we don’t understand everything right away.

Practice routine reflections as an essential part of the learning process. This routine can vary depending on the task or assignment that students are reflecting upon; however, the notion is the same—reflecting on and thinking about how we learn helps us to understand strategies that work or don’t work for us in any given task. Elementary teachers may ask students to consider what went well during their learning process. What do they wish they had done differently having now finished the task? What was the most difficult aspect of the assignment or project? How did they use their strengths to complete this assignment? Questions like these allow elementary students to not only reflect on their learning process, but also take deliberate ownership over their work. Through reflection, young learners find value in the challenges and errors, which helps to keep the negative self-fulfilling prophecies at bay.