National Special Education Day: Instruction for Twice-Exceptional Students

The second day of December marks an important day in education. National Special Education Day may be widely unknown to most people outside of the classroom; however, its significance is notable. This special day, which officially began in 2005, marks the anniversary of the signing of our nation’s first special education law passed in 1975. IDEA, or the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, ensures that students with disabilities are entitled to Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) that suits their specific needs.

But what does this mean for twice-exceptional (2E) students? This type of unique learner, once referred to as GTLD (gifted/talented and learning disabled), requires specifically differentiated instruction beyond the typical special education accommodations. So what does this type of instruction look like in the classroom? Take a look below to see how best practices can ensure the success of twice-exceptional students.

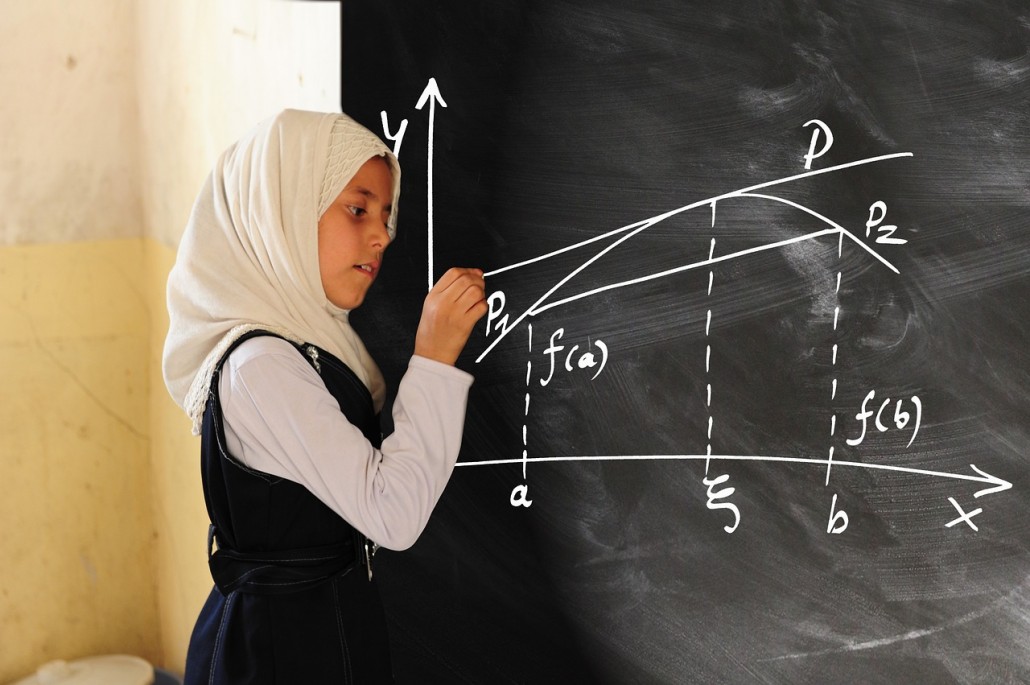

Twice-exceptional, previously referred to as GTLD, means that a student has been identified as gifted and also meets the criteria for an IEP or 504 plan. These students could have Asperger’s, vision or hearing impairment, ADHD, or an emotional or learning disability. While we know that every learner is unique, twice-exceptional students have an even more complex need for differentiation. These students often experience difficulties in processing speed, working memory, written expression, executive functioning, attention and self-regulation, and social skills. While these struggles could obviously interfere with learning, the flipside of 2E students is their unique strengths. Students are often articulate, advanced readers with advanced verbal skills. Their gifted verbal abilities mean that these students would greatly benefit from tasks and assessments where their mastery is measured orally. Instead of a research paper, essay, etc., provide these students with the opportunity to present their findings verbally, organize a speech, or participate in a debate. A simple spoken exam or assessment could prove much more beneficial than a written response or multiple choice test.

Because twice-exceptional students acquire knowledge and concepts quickly, they may appear bored or aloof in class. They are known for rapidly acquiring conceptual knowledge and have a natural ability to think critically. Because of this, review activities, rote memorization, and tasks involving simple recall are not preferred. These sorts of tasks have the potential to cause twice-exceptional students to “check out.” Anything that seems repetitive, elementary, or mundane will likely be received as irritatingly simple, causing 2E students to zone out or avoid the task all together.

2E students are typically inquisitive and thrive when exploring, questioning, or investigating. These students often have strengths in problem-solving. So, provide them with hands-on learning opportunities—tasks that allow them to deconstruct, build, or question the functionality of something, and play to their strengths and interests.

Twice-exceptional students tend to think that others see them as lazy, unmotivated, or stupid—this could not be farther from the truth. These students simply have different learning needs. For instance, 2E learners often find easy tasks to be difficult and difficult tasks to be easy. They may be able to build a perfectly proportional model bridge; however, if asked to explain how they arrived at the dimensions mathematically, they may struggle greatly. In these instances, the students simply “knew” how to complete the task or skill—but they will not be able to provide a detailed explanation of how they did it, or why. Because of this ability to simply “do,” 2E students thrive when given choices and differentiated opportunities to display their talents. This sort of strength-based learning means that they should be given opportunities for acceleration and enrichment, creative independent study, and study groups with other GT students.